I gave two paper presentations recently at the BSRLM day conference in Brighton. Abstracts and slides are below.

predictor for mathematics achievement. Nevertheless, findings are mixed whether this is more the case for other

I gave two paper presentations recently at the BSRLM day conference in Brighton. Abstracts and slides are below.

predictor for mathematics achievement. Nevertheless, findings are mixed whether this is more the case for other

I gave two paper presentations recently at the BSRLM day conference in Brighton. Abstracts and slides are below.

These are the slides to the keynote I did at CADGME 2016

This is the presentation I gave at ICME-13:

OPPORTUNITY TO LEARN maths: A curriculum approach with timss 2011 data

Christian Bokhove

University of Southampton

Previous studies have shown that socioeconomic status (SES) and ‘opportunity to learn’ (OTL), which can be typified as ‘curriculum content covered’, are significant predictors of students’ mathematics achievement. Seeing OTL as curriculum variable, this paper explores multilevel models (students in classrooms in countries) and appropriate classroom (teacher) level variables to examine SES and OTL in relation to mathematics achievement in the 2011 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS 2011), with OTL operationalised in several distinct ways. Results suggest that the combination of SES and OTL explains a considerable amount of variance at the classroom and country level, but that this is not caused by country level OTL after accounting for SES.

Full paper, slides:

This is a follow-up post from this post in which I unpicked one part of large education review. In that post I covered aspects of papers by Vardardottir, Kim, Wang and Duflo. In this post I cover another papers in that section (page 201).

Booij, A.S., E. Leuven en H. Oosterbeek, 2015, Ability Peer Effects in University: Evidencefrom a Randomized Experiment, IZA Discussion Paper 8769.

This is roughly the same as what is described in the article on page 20. The paper then also addresses average grade and dropout. Actually, the paper goes into many more things (teachers, for example) which I will not cover. It is interesting to look at the conclusions, and especially the abstract. I think the abstract follows from the data, although I would not have said “students of low and medium ability gain on average 0.2 SD units of achievement from switching from ability mixing to three-way tracking.” because it seems 0.20 and 0.18 respectively (so 19% as mentioned in the main body text). Only a minor quibble, which after querying, I heard has been changed in the final version. I found the discussion very limited. It is noted that in different contexts (Duflo, Carrell) roughly similar results are obtained (but see my notes on Duflo).

Overall, I find this an interesting paper which does what it says on the tin (bar some tiny comments). Together with my previous comments, though, I would still be weary about the specific contexts.

This paper has the title “Is traditional teaching really all that bad?” and is by Schwerdt and Wuppermann makes clear that this paper sets out to show it isn’t. And without this paper I would have said the same thing. Simply because I wouldn’t deny that ‘direct instruction’ has had a rough treatment in the last decades.

There are several versions of this paper on SSRN and other repositories. The published version is from ‘Economics of Education Reviw’, and this immediately shows why I have included it. In the advent of economics papers some have preferred to use this paper rather than a more sociological, psychological or education research approach.

The literature review is, as often the case in my opinion in economics papers, a bit shallow. The study uses TIMSS 2003 year 8 data (I don’t know why they didn’t use 2007 data).

I find the wording “We standardize the test scores for each subject to be mean 0 and standard deviation 1.” a bit strange because the TIMSS dataset, as in later years, does not really have ‘test scores per subject’ because subjects do not make all the assessment items.

(link)Instead, there are five so-called ‘plausible values’. Not using them might underestimate the standard error, which might lead to results being significant more swiftly. This variable is the outcome, another variable is the question 20.

(link)Instead, there are five so-called ‘plausible values’. Not using them might underestimate the standard error, which might lead to results being significant more swiftly. This variable is the outcome, another variable is the question 20.

The distinction between instruction and problem solving are based on three of these items: b is seen as direct instruction, c and d together problem solving (note that one of course does mention ‘guidance’). There is an emphasis on ‘new material’ so I can see why these are chosen. Of course the use of percentages means that an absolute norm is not apparent, but I can see how lecture%/(lecture%+problemsolving%) denotes a ratio of lecturing. The other five elements are together used as control. Mean imputation was used (I can agree that imputation method probably did not make a difference) and sample weights (also good, contrary to no plausible values).

The distinction between instruction and problem solving are based on three of these items: b is seen as direct instruction, c and d together problem solving (note that one of course does mention ‘guidance’). There is an emphasis on ‘new material’ so I can see why these are chosen. Of course the use of percentages means that an absolute norm is not apparent, but I can see how lecture%/(lecture%+problemsolving%) denotes a ratio of lecturing. The other five elements are together used as control. Mean imputation was used (I can agree that imputation method probably did not make a difference) and sample weights (also good, contrary to no plausible values).

Table 1 in the paper tabulates all the variables and shows some differences between maths and science teachers, for example in the intensity of lecture style teaching. The paper then proposes a model “standard education production function”. In all the result tables we can certainly see the standard p=.10 and again with large N’s this, to me, seems unreasonable. A key result is in Table 4:

The first line is the lecture style teaching variable. Columns 1 and 3 show that Math is significant (but keep in mind, at 5% with high N. However, 0.514 does sound quite high) and Science is not. Columns 2 and 4 then have the same result but now by taking into account school sorting based on unobservable characteristics of students through inclusion of fixed school effects. I find the pooling a bit strange, and reminds me of the EEF pooling of maths mastery for primary and secondary to gain statistically significant results. Yes, here too, both subjects then yield significant results. Together with the plausible values issue I would be cautious.

The first line is the lecture style teaching variable. Columns 1 and 3 show that Math is significant (but keep in mind, at 5% with high N. However, 0.514 does sound quite high) and Science is not. Columns 2 and 4 then have the same result but now by taking into account school sorting based on unobservable characteristics of students through inclusion of fixed school effects. I find the pooling a bit strange, and reminds me of the EEF pooling of maths mastery for primary and secondary to gain statistically significant results. Yes, here too, both subjects then yield significant results. Together with the plausible values issue I would be cautious.

Table 5 extends the analysis.

The same pattern arises. The key variable is significant at the questionable 10% level (column 1) and a bit stronger after adding confounding variables (at the 5% level, but again with high N). The articles notices that over the columns the variable is quite constant, but also that it’s lower than the Table 4 results, showing that there are school effects.

The same pattern arises. The key variable is significant at the questionable 10% level (column 1) and a bit stronger after adding confounding variables (at the 5% level, but again with high N). The articles notices that over the columns the variable is quite constant, but also that it’s lower than the Table 4 results, showing that there are school effects.

There is footnote on page 373 that might have received a bit more attention. I find the reporting a bit strange because the first line indicates that variable ranges from 0.11 to 0.14, not 0.14 to 0.1 (and why go from a larger to a smaller number, is this a typo?). Overall, 1% of an SD seems very low. I think the discussion that follows is interesting and adds some thoughts. I thought it was interesting that was said “Our results, therefore, do not call for more lecture style teaching in general. The results rather imply that simply reducing the amount of lecture style teaching and substituting it with more in-class problem solving without concern for how this is implemented is unlikely to raise overall student achievement in math and science.”. Well, that does seem a balanced conclusion, indeed. And again, a strong feature for most economic papers, the robustness checks are good.

There is footnote on page 373 that might have received a bit more attention. I find the reporting a bit strange because the first line indicates that variable ranges from 0.11 to 0.14, not 0.14 to 0.1 (and why go from a larger to a smaller number, is this a typo?). Overall, 1% of an SD seems very low. I think the discussion that follows is interesting and adds some thoughts. I thought it was interesting that was said “Our results, therefore, do not call for more lecture style teaching in general. The results rather imply that simply reducing the amount of lecture style teaching and substituting it with more in-class problem solving without concern for how this is implemented is unlikely to raise overall student achievement in math and science.”. Well, that does seem a balanced conclusion, indeed. And again, a strong feature for most economic papers, the robustness checks are good.

In conclusion, I found this an interesting use of a TIMSS variable. Perhaps it could be repeated with 2011 data, and now include all five plausible values (perhaps a source of error). Nevertheless, although I think strong conclusions in favour of lecturing could be debated, likewise it could be said that there also are no negative effects of it: there’s nothing wrong with lecturing!

One of the papers that made a viral appearance on Twitter is a paper on behaviour in the classroom. Maybe it’s because of the heightened interest in behaviour, for example demonstrated in the DfE’s appointment of Tom Bennett, and behaviour having a prominent place in the Carter Review.

Carrell, S E, M Hoekstra and E Kuka (2016) “The long-run effects of disruptive peers”, NBER Working Paper 22042. link.

The paper contends how misbehaviour (actually, domestic violence) of pupils in a classroom apparently leads to large sums of money that people will miss out of later in life. There, as always, are some contextual questions of course: the paper is about the USA, and it seems to link domestic violence with classroom behaviour. But I don’t want to focus on that, I want to focus on the main result in the abstract: “Results show that exposure to a disruptive peer in classes of 25 during elementary

school reduces earnings at age 26 by 3 to 4 percent. We estimate that differential exposure to children

linked to domestic violence explains 5 to 6 percent of the rich-poor earnings gap in our data, and that

removing one disruptive peer from a classroom for one year would raise the present discounted value

of classmates’ future earnings by $100,000.”.

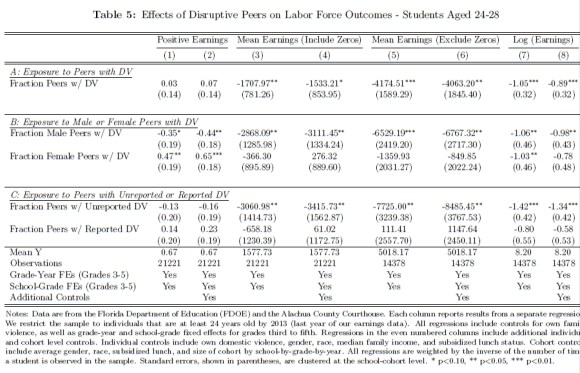

It’s perfectly sensible to look at peer effects of behaviour of course, but monetising it -especially with a back of envelope calculation (actual wording in the paper!)- is on very shaky ground. The paper respectively looks at the impact on test scores (table 3), college attendance and degree attainment (table 4), and labor outcomes (table 5). The latter is also the one reported in the abstract.

There are some interesting observations here. The abstract’s result is mentioned in the paper “Estimates across columns (3) through (8) in Panel A indicate that elementary school exposure to one additional disruptive student in a class of 25 reduces earnings by between 3 and 4 percent. All estimates are significant at the 10 percent level, and all but one is significant at the 5 percent level.” The fact economists would even want to use 10% (with such a large N) is already strange to me. Even 5% is tricky with those numbers. However, the main headline in the abstract can be confirmed. But have a look at panel C. It seems there is a difference between ‘reported’ and ‘unreported’ Domestic Violence. Actually, reported DV has a (non-significant) positive effect. Where was that in the abstract? Rather than a conclusion along the lines whether DV was reported or not, the conclusion only focuses on the negative effects of *unreported* DV. I think it would be more fair to make a case for better signalling and monitoring of DV, so that negative effects of unreported DV are countered; after all, there are no negative effects on peers when reported.

There are some interesting observations here. The abstract’s result is mentioned in the paper “Estimates across columns (3) through (8) in Panel A indicate that elementary school exposure to one additional disruptive student in a class of 25 reduces earnings by between 3 and 4 percent. All estimates are significant at the 10 percent level, and all but one is significant at the 5 percent level.” The fact economists would even want to use 10% (with such a large N) is already strange to me. Even 5% is tricky with those numbers. However, the main headline in the abstract can be confirmed. But have a look at panel C. It seems there is a difference between ‘reported’ and ‘unreported’ Domestic Violence. Actually, reported DV has a (non-significant) positive effect. Where was that in the abstract? Rather than a conclusion along the lines whether DV was reported or not, the conclusion only focuses on the negative effects of *unreported* DV. I think it would be more fair to make a case for better signalling and monitoring of DV, so that negative effects of unreported DV are countered; after all, there are no negative effects on peers when reported.

It feels as if there has been an incredible surge of econometric papers in social media. Like a lot of research they sometimes are ‘pumped around’ uncritically. Sometimes it’s the media, sometimes it’s a press release from the university, sometimes it’s even the researchers themselves who seem to want a ‘soundbite’. These econometric papers are fascinating. What they often have going for them -according to me- is their strong, often novel, mathematical models (for example Difference in Differences or Regression Discontinuity Design. I also like how after presenting results there often are ‘robustness’ sections. However, they also often lack a sufficient literature overview; one that often is biased towards econometric papers (yet, it is quite ‘normal’ that disciplines cite within disciplines). Also, conclusions, in my view, lack sufficient discussion of limitations. Finally, I often find that the interpretation of the statistics is a bit ‘typical’, in that econometric papers seem to love to use significance testing (NHST) with p=.10 (yes, I know of criticisms of NHST) and try to summarize the findings in a rather ‘simplistic’ way. The latter might be caused by an unhealthy academic ‘publish or perish’ culture in which we sometimes feel only extraordinary conclusions are worth publishing (publication bias).

Some people have asked me what I look for in such papers. In this first blog I will use some papers from a recent report of the CPB, the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis. They recently released a report on education policy, summarizing the effectiveness of all kinds of educational policies. As the media loved to quote on a section on ability grouping, who seemed to say that ‘selection worked’, I focused on that part. It also was the topic of a panel discussion at researchEd maths and science, so it also was something I had looked into any way. The research is mixed. It struck me that, as could be expected from an economic policy unit, the studies were almost all economically oriented. Of course some went as far as suggesting that the review just had high standards and that maybe therefore educational and sociological research did not make the cut (because of inclusion criteria, see p. 330 of the report, in Dutch). This all-too positive view of economic research, and less so of other research, in my view is unwarranted. It has more to do with traditions within disciplines. In this case I want to tabulate some of my thoughts about the papers around ability grouping within one type of education (p. 200 of the report). I won’t go into the specifics of the Dutch education system but it suffices to say that the Netherlands has several ‘streams’ based on ability, but within the streams students are often grouped by mixed ability. This section wanted to look at studies that looked at ability grouping within each of those streams. The media certainly made it that way.

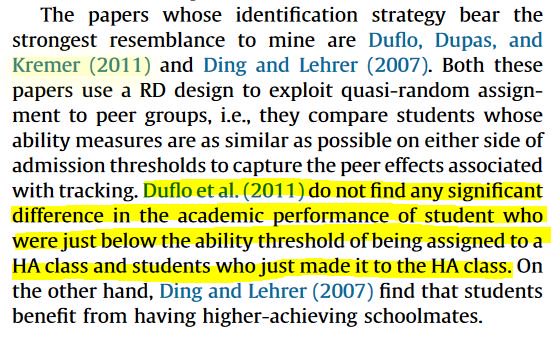

The study that I recognized, as it featured in the Education Endowment Fund toolkit, was the paper by Duflo et al. It is a study of primary schools in Kenya.

Duflo, E., P. Dupas en M. Kremer, 2011, Peer effects, teacher incentives, and the impact of tracking: evidence from a randomized evaluation in Kenya, American Economic Review, vol. 101(5): 1739-1774.

The paper first had been published as an NBER working paper. There is a difference in the wording of the abstracts of working and published paper, but in both cases the main effect is:

In sum, I think we would need to be a bit careful in concluding ‘ability grouping’ works.

Interestingly, Vardardottir points out the non-significant findings of Duflo et al., although in a preliminary paper there was a bit more discussion about the original Duflo et al. working paper. Maybe this is about different results, but I thought it was poignant.

The study, conducted in Iceland and in secondary school (16 yr olds) finds “Being assigned to a high-ability class increases academic achievement”. I thought there was a lot of agreement between the data and the findings. The study is about ‘high ability classes’ and the CPB report says exactly that. This seems to correspond with educational research reviews as well: the top end of ability might profit from being in a separate ability group. However, a conclusion about ability grouping ‘in general’ for all ability groups is difficult to make here.

The study, conducted in Iceland and in secondary school (16 yr olds) finds “Being assigned to a high-ability class increases academic achievement”. I thought there was a lot of agreement between the data and the findings. The study is about ‘high ability classes’ and the CPB report says exactly that. This seems to correspond with educational research reviews as well: the top end of ability might profit from being in a separate ability group. However, a conclusion about ability grouping ‘in general’ for all ability groups is difficult to make here.

Vardardottir, A., 2013, Peer effects and academic achievement: A regression discontinuity approach, Economics of Education Review, vol. 36: 108-121.

A third paper mentioned in the report is one by Kim et al.. Another context: secondary school, and one set in South Korea. It concludes that: “First, sorting raises test scores of students outside the EP areas by roughly 0.3 standard deviations, relative to mixing. Second, more surprisingly, quantile regression results reveal that sorting helps students above the median in the ability distribution, and does no harm to those below the median.”. As an aside, it’s interesting to see that the paper had already been on SSRN (now bought by Elsevier) since 2003. This begs the question, of course, from what year the data is. This always is a challenge; peer review takes time and often papers concern situations from many years before. In the meantime things (including policies) might have changed.

Kim, T., J.-H. Lee en Y. Lee, 2008, Mixing versus sorting in schooling: Evidence from the equalization policy in South Korea, Economics of Education Review, vol. 27(6): 697-711.

The paper uses ‘Difference-in-Differences’ techniques. I think the overall effect (the first conclusion), based on this approach is quite clear. I personally don’t find this very surprising (yet) as most literature tends to confirm that positive effect. However, criticism to it often is along the lines of equity i.e. like Vardardottir high ability profiting most from this, with lower ability not profiting or being even worse off. Interestingly (the authors also say ‘surprisingly’), the quantile regression seems to go into that:

The footnote summarizes the findings. If I understand correctly, the argument is that with controls, column (2) gives the overall effect per quantile of the ability grouping. This is clear: at 1% significant effects for all groups. The F-value at the bottom tests for significant differences, and is not significant (>.1, yes economists use 10%), hence the statement ‘no significant differences’ between different abilities. Based on column (2) one could say that; we could of course also say that a difference of .320SD versus .551SD is rather large. But what’s more interesting, is the pattern of significant effects over the subjects: those are all over the place in two ways. Firstly, in the differential effects on the different ability groups e.g. in English significantly larger positive effects higher ability than lower ability (just look at the number of *), in Korean significantly more negative effects for lower ability. (Note, that I did see that other control variables weren’t included here, I don’t know why, there is something interesting going on here any way, as there are differences first in column (1) but controls in (2) make them non-significant). Furthermore, the F-values at the bottom show that only for maths there are no significant differences, for all the other subjects there are, some quite sizable. What seems to be happening here is that all the positive and negative effects over the ability groups roughly cancel each other out, yielding no significant difference. Maybe they go away when including controls, but that can’t be checked. What is clear, I think, is that there are differences between subjects. I think the conclusion in the abstract “sorting helps students above the median in the ability distribution, and does no harm to those below the median” therefore needs further nuance.

The footnote summarizes the findings. If I understand correctly, the argument is that with controls, column (2) gives the overall effect per quantile of the ability grouping. This is clear: at 1% significant effects for all groups. The F-value at the bottom tests for significant differences, and is not significant (>.1, yes economists use 10%), hence the statement ‘no significant differences’ between different abilities. Based on column (2) one could say that; we could of course also say that a difference of .320SD versus .551SD is rather large. But what’s more interesting, is the pattern of significant effects over the subjects: those are all over the place in two ways. Firstly, in the differential effects on the different ability groups e.g. in English significantly larger positive effects higher ability than lower ability (just look at the number of *), in Korean significantly more negative effects for lower ability. (Note, that I did see that other control variables weren’t included here, I don’t know why, there is something interesting going on here any way, as there are differences first in column (1) but controls in (2) make them non-significant). Furthermore, the F-values at the bottom show that only for maths there are no significant differences, for all the other subjects there are, some quite sizable. What seems to be happening here is that all the positive and negative effects over the ability groups roughly cancel each other out, yielding no significant difference. Maybe they go away when including controls, but that can’t be checked. What is clear, I think, is that there are differences between subjects. I think the conclusion in the abstract “sorting helps students above the median in the ability distribution, and does no harm to those below the median” therefore needs further nuance.

Therefore it was useful there was a follow-up article by Wang. One thing addressed here is the amount of tutoring: an example of how different disciplines could complement each other i.e. Bray’s work on Shadow Education.

Wang, L. C., 2014, All work and no play? The effects of ability sorting on students’ non-school inputs, time use, and grade anxiety, Economics of Education Review, vol. 44: 29-41.

The article is, however, according to the CPB report premised on the assumption that there are null effects on lower-than-average-ability. Effects that, in my view, already deserve nuance based on subject differences. It therefore is very interesting that Wang looks at tutoring, homework etc. but the article seems to not continue with subject differences. This is a shame, in my view, because from my on mathematics education background -and as stated at that researchEd maths and science panel- I can certainly see how maths might be different to languages. It would have been a good opportunity to also think about top performance of Korea in international assessments, for example. Yet the take-away message for the CPB seems to be ‘ability grouping works’.

There are more references, which I will try to unpick in future blogs. These will also include papers on teaching style, behavior etc. all education topics for which people have promoted economics papers as ‘definitive proof’. There also are multiple working papers (the report argues that because some series often end up as peer-reviewed articles any way, they might be included, like NBER and IZA papers.) which I might cover.

Nevertheless, this first set of papers, in my view, does not really warrant the conclusion ‘ability groups work’. Though to be fair, in many cases the abstracts might make you think differently. It shows that actually reading the original source material can be important. Yet, even if we assume they do say this, the justification that follows at the end of the paragraph is strange (translated): “The literature stems, among others, from secondary education and, among others, from comparable Western countries. The results point in the same direction, disregarding school type or country. That’s why we think the results can be translated to the Dutch situation.”. Really? Research from primary, secondary and higher education (that’s the Booij one). From Kenya, from Korea (with its shadow education)?

What we have here is a large variety of educational contexts, both in school type(s), years and countries, with confusing presentation of findings with, in my view, questionable p-value. OK, now I’m being facetious; I just want people to realize that every piece of research has drawbacks. They need to be acknowledged, just like the strong(er) points. If we see quality of research as a dimension from ‘completely perfect’ (would be hard-pressed to find that) and ‘completely imperfect’, there are many many shades in-between. ‘Randomized’ is often seen as a gold standard (I still feel that this also comes with issues but that is for another blog), yet economists have deemed all kinds of fine statistical techniques as ‘quasi experimental’ and therefore ‘still good enough’. Yet, towards other disciplines there sometimes seems to be a ‘rigor’ arrogance. Likewise, other disciplines too readily dismiss some sound economics research because it seldom concerns primary data collection or they ‘summarize’ data incorrectly. It almost feels like a clash of the paradigms. I would say it depends on what you want to find out (research questions). The research questions need to be commensurate with your methodology, and they in turn both need to fit the (extent of) the conclusions. We can learn a lot from each other, and I would encourage disciplines to work together, rather than play ‘we are rigorous and you are not’ or ‘your models are crap’ games. Be critical of both (as I am above, note I’m just as critical about any piece of research without disregarding its strengths), be open to affordances of both (and more disciplines of course), and let’s work together more.

Presentation for researchED maths and science on June 11th 2016.

References at the end (might be some extra references from slides that were removed later on, this interesting 🙂

Interested in discussing, contact me at C.Bokhove@soton.ac.uk or on Twitter @cbokhove

Dit is de researchED presentatie die ik gaf op 30 Januari 2016 in Amsterdam. Enkele Engelstalige woorden zijn er in gelaten. Literatuur is aan het einde toegevoegd.