This blog is adapted from a long thread on twitter. I thought it was useful to test how swiftly I could turn it into a blog. You can probably notice in the language.

Ok, some thoughts on E.D.Hirsch’s latest book. To be honest, I’ve seen/heard 4 or 5 interviews with him so some of that might be mixed in. Let me begin by saying that it’s quite clear that a desire for social justice really drives Hirsch. I seems passionate in both audio and writing. Several people, including himself, gave called this (last) book his most pronounced. I can see that but I do think because of that some facts suffer. This is why I thought it wasn’t as good as ‘Why knowledge matters’ (I wrote bokhove.net/2017/02/17/hir… about that book). There is overlap with that book. I wonder how many edutwitter books by now have reported on De Groot and Chase and Simon’s chess research…On the whole, I thought the themes were quite fragmented in that the book connects a lot of seemingly disconnected topics.

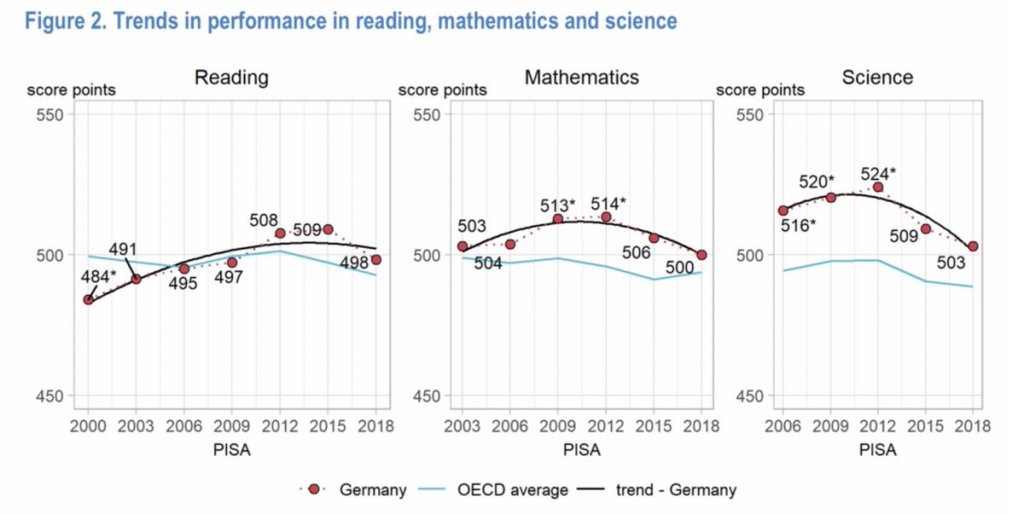

Some points in chapter 1 interesting (although I don’t know enough about ethnicity and culture to really comment) but also, I thought, an exaggeration of the US crisis (at least, based on PISA). “The nations that moved ahead of us had taken note from PISA of their shortcomings in schooling, and they improved their results. We continue downward.” (p. 23). Really? (From the US country notes)

And what about TIMSS and PIRLS? Sure, you might still be able to make a case things are not going well, but if you rely so much on such scores (see chapter 6 as well) then this isn’t very strong, in my opinion.

By the way, in chapter 2 the PISA claim is repeated:

“On the international PISA test for fifteen- year- olds, the scores of US children and their relative ranking have both been sinking ever since 2000, when the scores started being recorded. “ – so here it is again.

Chapter 2 are interviews/conversations with two teachers. They are interesting. I think they ideologically nicely juxtapose their previous and current beliefs. But they are anecdotal. And in my opinion a caricature of ‘child-centered classrooms’. Also very US focussed (understandable). All in all, although I enjoyed reading the interviews, I was wondering what support they actually gave for the central thesis of the book. Not so much, I thought.

Chapter 3 focuses on evidence on shared-knowledge schools. A lot is made of a study by Grissmer but I haven’t been able to locate it. If you do, please let me know. Hirsch says “These are decisive results.” but we need to be able to then read it. A footnote says “These are decisive results: The results were reported by Professor Grissmer in a recent public lecture at a school conference in Denver. I eagerly await publication!” – unsatisfactory. It would have been good to put some more references re charters and knowledge-curricula. To my knowledge they are quite mixed. That’s why it’s so important, in my opinion, to look at the details. On Charter schools Fryer’s work or Chabrier maybe nber.org/papers/w22390 Or the older Datnow et al. jstor.org/stable/1002341…

An EEF trial: bera-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.100…

But sure, a book can’t mention everything. But to have the argument to revolve around a-yet-to-be-published study… Chapter 4 is about teacher training institutions. Thought that was quite one-sided and possibly very US-centric. But the classics are there: Dewey, constructivism and then Kirschner, Sweller & Clark of course. Would have liked more discussion. Chapter 5 underlines what Hirsch I think has mentioned numerous times in the interviews as well: ‘according to brain science’. There’s quite some overlap, IIRC, with ‘Why Knowledge Matters’. There are some interesting references here. But for a claim ‘according to science’ I thought ‘blank slate’ was quite limited. Maybe ‘the nature of nurture’ would be appropriate. Ericsson comes by again with a similar line as in his previous book. I’m not sure if it is a completely correct representation of his work. This also is the chapter with chess research again and reading comprehension. I think most of you might know that I think the ‘only domain-specific’ claim is not correct. Chi, Ohlsson, Abrami, Kaufman, and more would give a picture where skills are ‘practical knowledge’, rooted in domain knowledge but with generic elements.

Chapter 6 gives an international perspective, so potentially for my International Largescale Assessment focus the most interesting.

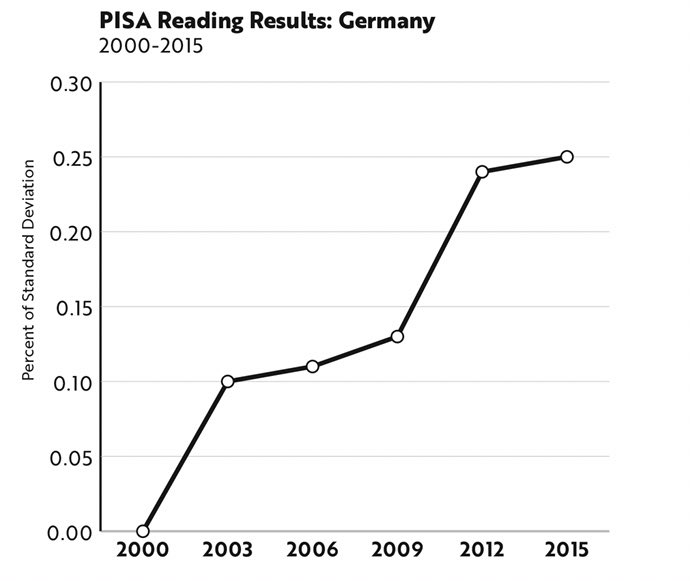

Unfortunately, it has several issues. Firstly, it is often just stated that a curriculum is or is not ‘knowledge-focussed’, seldom with a robust analysis or description of that curriculum (just like the previous book for Sweden and France). Secondly, even if you would pin down the curriculum, you also need to know other education system variables. But even then, most of the PISA data is tricky for causal claims. As a result, the inferences are shaky. This is the graph for Germany: “The path still continues upward” – seems legit for reading.

But December 2019 PISA 2018 results and what about other subjects? Plus the lag from reforms and scores. And an analysis of *how* we know Germany “instituted what was in effect a shared- knowledge national curriculum in each grade of elementary school.” – has it now worn off?

We had already seen the imo incorrect US pisa analysis. And then for Sweden again huge assumptions about effects. But for Hirsch these are just a prologue to “That prediction turns to a near certainty when we consider the example of France.”. Now, similar arguments hold for France. I previously had written about it as it was in the previous book as well

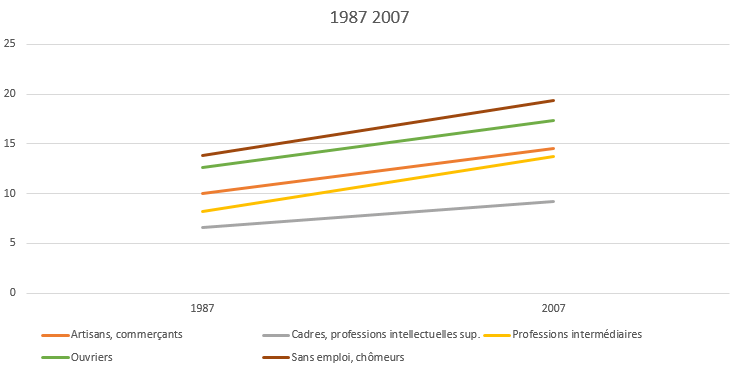

It starts with “These national data are scientifically more compelling than any contrived experiment could ever be, because of the large number of subjects sampled in the PISA scores.” (p. 133) – not sure what Hirsch means here re the argument he had just built up. For this analysis I think it was only a fairly limited verbal test. As far as I know, it’s not a lab experiment. But anyway, those scores do indeed show a decrease. Not sure how you can causally claim the Loi Jospin did that. But Hirsch’s claims have always been about inequality as well. Hirsch has evidenced this better this time, but the irony is that it does uncover an error in the previous diagram (in ‘Why Knowledge Matters’).

The new diagram is better because it is taken directly from French sources. However, this graph was published after his previous book.

But compare the previous diagram and this one. On the left ‘laborers’ and ‘unemployed’ seem switched. In the blog I had already mentioned not all categories were there.

And although 1997 is included now, 2015 wasn’t. Of course you could argue that the curriculum effects Hirsch focussed on weren’t relevant any more for France, but as 2015 was relevant for the other countries, I would have included it. *Especially* because the book does quite a strange thing of *mirroring* the trajectory of the scores towards the future, and then saying ‘this is what you’d get if you do a shared-knowledge curriculum’. So all years covered, except the existing 2015 data points.

The final chapters/part are/is about commonality and patriotism. I recognised the community focus from the previous book. I like that. I’m not so convinced, though, that ‘patriotism’ is the best way to build such (speech) communities. Of course, you *can* go on the ‘patriotism is fine’ tour, but to be honest I don’t understand why you really would want to venture that way, when you’ve already got a strong ‘community’ argument. Or ‘tribe’ arguments.

Ok, that’s enough, lest I get memes a la ‘lengthier than the book itself’. 😎

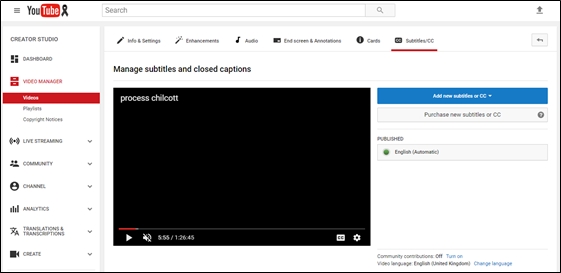

Like so many people I’ve never really liked transcribing audio, for example from interviews or focus groups. It is time-consuming and boring. Of course, you can outsource this but that unfortunately costs money. So I thought: “how can I do this quicker with available services.”

Like so many people I’ve never really liked transcribing audio, for example from interviews or focus groups. It is time-consuming and boring. Of course, you can outsource this but that unfortunately costs money. So I thought: “how can I do this quicker with available services.”